Chapter 4: Thermodynamic Constraints

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God."

— John 1:1, ESV

Claude Shannon's foundational insight linked information to thermodynamic entropy through the equation H = -Σp(i)log₂p(i), where H represents informational entropy and p(i) the probability of state i. This connection reveals why the spontaneous generation of complex specified information violates fundamental physical principles.

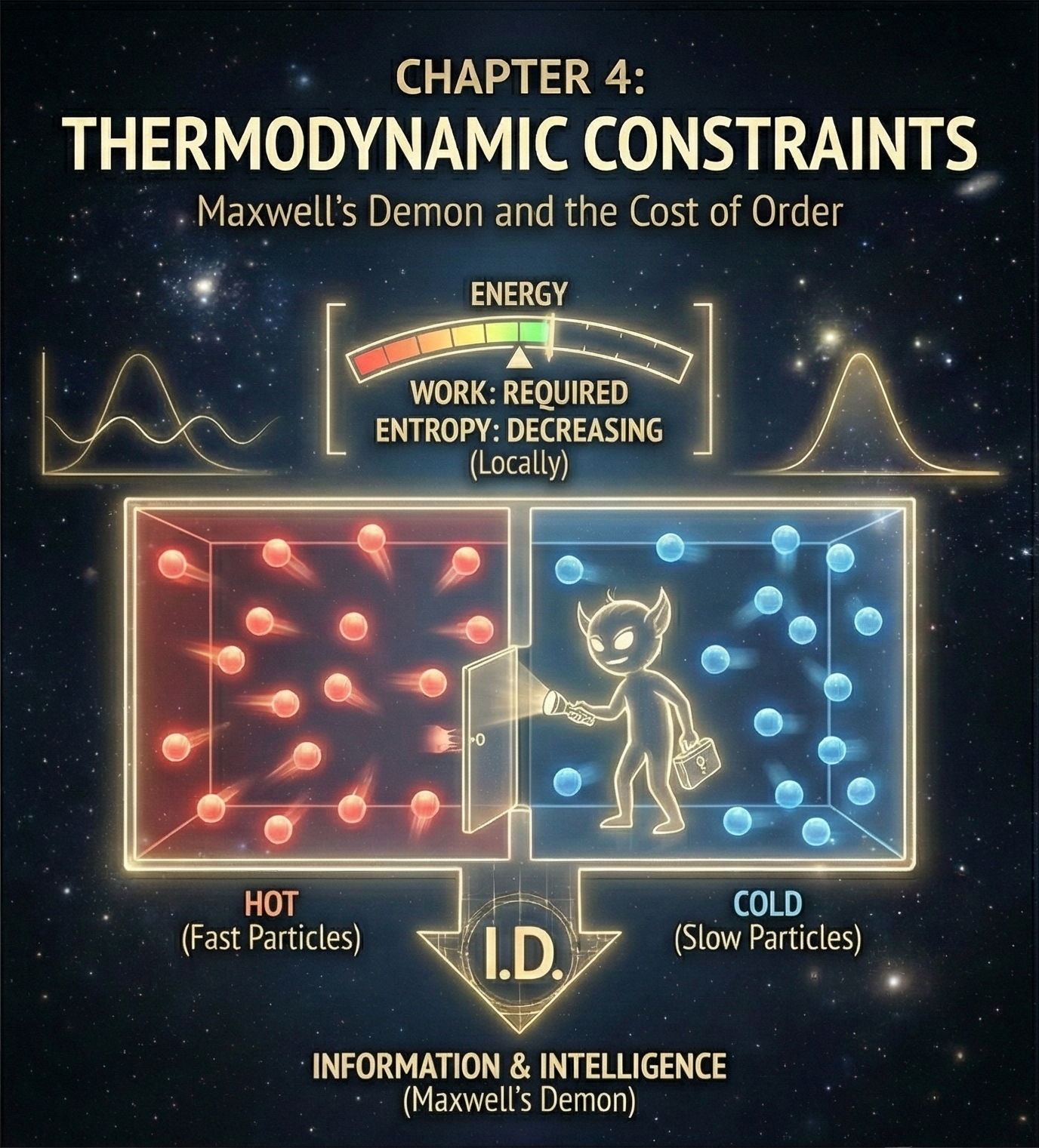

Maxwell's demon thought experiment illuminates the thermodynamic cost of information processing. To sort molecules by velocity—creating macroscopic order from microscopic chaos—the demon must measure molecular velocities and store that information in memory. Rolf Landauer proved that erasing information to reset the demon's memory necessarily dissipates heat, preserving the second law of thermodynamics.

But Landauer's principle reveals something profound: information processing requires energy expenditure precisely because information represents a form of order that runs counter to thermodynamic equilibrium. Creating specified information demands work against the entropic gradient—work that can only be performed by systems already possessing the informational resources necessary to direct energy toward functional outcomes.

This creates what we might term 'the informational paradox of origins.' Any naturalistic account of life's emergence must explain how molecular systems acquired the informational content necessary to resist entropic decay. Yet information-processing capabilities are themselves complex functional systems that require pre-existing information to specify their organization.

Ilya Prigogine's far-from-equilibrium thermodynamics demonstrates that open systems with energy fluxes can form ordered structures—crystals, convection cells, vortices, chemical oscillators—without intelligence. Non-equilibrium thermodynamics already predicts such self-organization, and these pattern-forming systems clearly demonstrate that energy flow can generate macroscopic order from microscopic randomness. The claim here is more specific: to get a system that stores task-specific information, uses that information via a decoding mechanism, and maintains functionally coherent organization across scales, you need not just low entropy but highly structured constraints. Such systems exhibit aperiodic complexity characteristic of functional biological information, which differs fundamentally from the simple periodic or quasi-periodic patterns of non-living self-organization.

The crucial distinction lies in algorithmic compressibility. Prigogine structures can be described by simple mathematical equations with few parameters. Biological information systems resist such compression, requiring detailed specification of their organizational states. A complete description of ribosomal function demands knowledge of RNA sequences, protein structures, assembly pathways, and regulatory mechanisms—information that cannot be compressed into simple generating algorithms. Maxwell's demon and Landauer's principle show that information processing has thermodynamic costs; the point is that biological information processing realizes an astonishingly precise, multi-layered constraint architecture that pushes us far beyond generic self-organization.

Bernd-Olaf Küppers' thermodynamic analysis of molecular evolution demonstrates that functional biopolymers exist in 'sequence spaces' where the vast majority of sequences lack any functional capability. Evolution through random mutation and natural selection must navigate these spaces by crossing fitness valleys where intermediate sequences confer no selective advantage.

The mathematical topology of these fitness landscapes proves crucial. Douglas Axe's experiments reveal that functional protein sequences are separated by expanses of non-functional sequences too vast to cross through random walk processes. The probability of finding new functional sequences by random mutation approaches zero for proteins longer than 150 amino acids.

More fundamentally, Michael Behe's concept of irreducible complexity identifies biological systems where function depends on the coordinated interaction of multiple components, none of which provides any functional advantage in isolation. Such systems cannot emerge through gradual Darwinian processes because intermediate stages lack the selective advantage necessary to fix beneficial mutations in populations.

The bacterial flagellum exemplifies irreducible complexity at the molecular level. Its rotary motor requires coordination among dozens of proteins—stators, rotors, drive shafts, universal joints, and propellers—each precisely engineered for its specific function. Removing any component destroys motility, eliminating the selective advantage that supposedly drove the system's evolution.

Scott Minnich's genetic knockout experiments confirm this irreducibility empirically. Systematic deletion of flagellar genes demonstrates that the minimal functional flagellum requires approximately 30 proteins, with no viable evolutionary pathway through intermediate stages of reduced complexity.

The thermodynamic analysis thus reveals biological information systems as islands of negative entropy maintained against thermodynamic equilibrium through sophisticated molecular machinery that itself exhibits specified complexity. This creates a hierarchical bootstrap problem: complex systems maintaining the information necessary to maintain complex systems, with no naturalistic mechanism capable of initiating the hierarchy.

The resolution requires recognizing information as a fundamental category irreducible to matter and energy—a category that points beyond the material universe to the transcendent intelligence capable of instantiating specified complexity in thermodynamic systems inherently disposed toward randomness and decay.